|

PELAGIC FISH

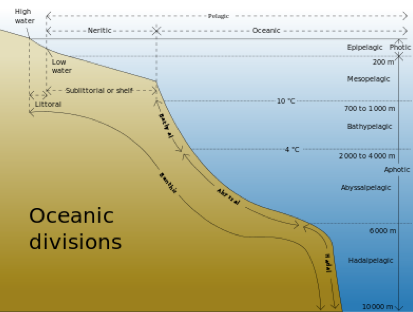

Pelagic fish live in the pelagic zone of ocean or lake waters - being neither close to the bottom nor near the shore - in contrast with demersal fish, which do live on or near the bottom, and reef fish, which are associated with coral reefs

The marine pelagic environment is the largest aquatic habitat on Earth, occupying 1,370 million cubic kilometres (330 million cubic miles), and is the habitat for 11 percent of known fish species. The oceans have a mean depth of 4000 metres. About 98 percent of the total water volume is below 100 metres, and 75 percent is below 1000 metres.

Marine pelagic fish can be divided into pelagic coastal fish and oceanic pelagic fish. Coastal fish inhabit the relatively shallow and sunlit waters above the continental shelf, while oceanic fish (which may well also swim inshore) inhabit the vast and deep waters beyond the continental shelf.

Pelagic fish range in size from small coastal forage fish, such as herrings and sardines, to large apex predator oceanic fishes, such as the Southern bluefin tuna and oceanicsharks. They are usually agile swimmers with streamlined bodies, capable of sustained cruising on long distance migrations.

The Indo-Pacific sailfish, an oceanic pelagic fish, can sprint at over 110 kilometres per hour. Some tuna species cruise across the Pacific Ocean. Many pelagic fish swim in schools weighing hundreds of tonnes. Others are solitary, like the largeocean sunfish weighing over 500 kilograms, which sometimes drift passively with ocean currents, eating jellyfish. |

Coastal fish |

|

Coastal fish (also called neritic or inshore fish) inhabit the waters near the coast and above the continental shelf. Since the continental shelf is usually less than 200 metres deep, it follows that coastal fish that are not demersal fish are usually epipelagic fish, inhabiting the sunlit epipelagic zone.

Coastal epipelagic fish are among the most abundant in the world.

They include forage fish as well as the predator fish that feed on them. Forage fish thrive in those inshore waters where high productivity results from the upwelling and shoreline run off of nutrients.

Some are partial residents that spawn in streams, estuaries and bays, but most complete their life cycle in the zone. |

|

Oceanic fish |

|

Oceanic fish inhabit the oceanic zone, which is the deep open water which lies beyond the continental shelves.

Oceanic fish (also called open ocean or offshore fish) live in the waters that are not above the continental shelf. Oceanic fish can be contrasted with coastal fish, which do live above the continental shelf. However, the two types are not mutually exclusive, since there are no firm boundaries between coastal and ocean regions, and many epipelagic fish move between coastal and oceanic waters, particularly in different stages in their life cycle.

Oceanic epipelagic fish can be true residents, partial residents, or accidental residents.

True residents live their entire life in the open ocean. Only a few species are true residents, such as tuna, billfish, flying fish, sauries, commercial pilot fish and remoras, dolphin, ocean sharks and ocean sunfish. Most of these species migrate back and forth across open oceans, rarely venturing over continental shelves. Some true residents associate with drifting jellyfish or seaweeds.

Partial residents occur in three groups: species which live in the zone only when they are juveniles (drifting with jellyfish and seaweeds); species which live in the zone only when they are adults (salmon, flying fish, dolphin and whale sharks); and deep water species which make nightly migrations up into the surface waters (such as the lantern fish).

Accidental residents occur occasionally when adults and juveniles of species from other environments are carried by accident into the zone by currents. |

|

Ocean sunfish

The huge ocean sunfish, a true resident of the ocean epipelagic zone, sometimes drifts with the current, eating jellyfish |

|

Whale shark

The giant whale shark, another resident of the ocean epipelagic zone, filter feeds on plankton, and periodically dives deep into the mesopelagic zone. |

|

Lantern fish

Lantern fish are partial residents of the ocean epipelagic zone. During the day they hide in deep waters, but at night they migrate up to surface waters to feed. |

|

|

|

Epipelagic fish

Large epipelagic predator fish, like this Atlantic blue fin tuna, have a deeply forked tail and a smooth body shaped like a spindle tapered at both ends and counter shaded with silvery colours. Small epipelagic forage fish, like this Atlantic herring, share the same body features listed for the predator fish above.

Epipelagic fish inhabit the epipelagic zone. The epipelagic zone is the water from the surface of the sea down to 200 metres. It is also referred to as the surface waters or the sunlit zone, and includes the photic zone. The photic zone is defined as the surface waters down to the point where the sunlight has attenuated to 1 percent of the surface value. This depth depends on how turbid the water is, but in clear water can extend to 200 metres, coinciding with the epipelagic zone. The photic zone has sufficient light for phytoplankton to photosynthese.

The epipelagic zone is vast, and is the home for most pelagic fish. The zone is well lit so visual predators can use their eyesight, is usually well mixed and oxygenated from wave action, and can be a good habitat for algae to grow. However, it is an almost featureless habitat. This lack of habitat diversity results in a lack of species diversity, so the zone supports less than 2 percent of the world's known fish species. Much of the zone lacks nutrients for supporting fish, so epipelagic fish tend to be found in coastal water above the continental shelves, where land runoff can provide nutrients, or in those parts of the ocean where upwelling moves nutrients into the area.

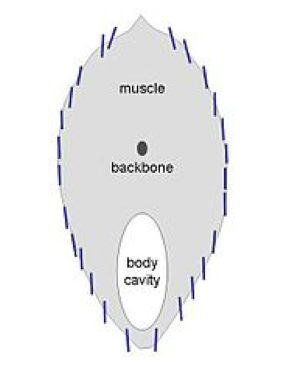

Epipelagic fish can be broadly divided into small forage fish and larger predator fish, which feed on them. Forage fish school and filter feed on plankton. Most epipelagic fish have streamlined bodies capable of sustained cruising on migrations. In general, predatory and forage fish share the same morphological features. Predator fish are usually fusiform with large mouths, smooth bodies, and deeply forked tails. Many use vision to predate zooplankton or smaller fish, while others filter feed on plankton. |

|

|

Most epipelagic predator fish and their smaller prey fish are counter shaded with silvery colours, which reduce visibility by scattering incoming light. The silvering is achieved with reflective fish scales that function as small mirrors. This can give an effect of transparency. At medium depths at sea, light comes from above, so a mirror oriented vertically makes animals such as fish invisible from the side.

In the shallower epipelagic waters, the mirrors must reflect a mixture of wavelengths, and the fish accordingly has crystal stacks with a range of different spacings. A further complication for fish with bodies that are rounded in cross-section is that the mirrors would be ineffective if laid flat on the skin, as they would fail to reflect horizontally. The overall mirror effect is achieved with many small reflectors, all oriented vertically.

Though the number of species is limited, epipelagic fishes are abundant. What they lack in diversity they make up in numbers. Forage fish occur in huge numbers, and large fish that predate on them are often sought after as premier food fish. As a group, epipelagic fishes form the most valuable fisheries in the world.

Many forage fish are facultative predators that can pick individual copepods or fish larvae out of the water column, and then change to filter feeding on phytoplankton when energetically that gives better results. Filter feeding fish usually use long fine gill rakers to strain small organisms from the water column. Some of the largest epipelagic fishes, such as the basking shark and whale shark are filter feeders, and so are some of the smallest, such as adult sprats and anchovies.

Ocean waters that are exceptionally clear contain little food. Areas of high productivity tend to be somewhat turbid from plankton blooms. These attract the filter feeding plankton eaters, which in turn attract the higher predators. Tuna fishing tends to be optimum when water turbidity, measured by the maximum depth a secchi disc can be seen during a sunny day, is 15 to 35 metres. |

The herring's reflectors are nearly vertical for camouflage from the side |

| Floating objects |

|

Drifting Sargassum seaweed provides food and shelter for small epipelagic fish. The small round spheres are floats filled with carbon dioxide, which provide buoyancy to the algae.

Epipelagic fish are fascinated with floating objects. They aggregate in considerable numbers around objects such as drifting flotsam, rafts, jellyfish and floating seaweed. The objects appear to provide a "visual stimulus in an optical void". Floating objects can offer some protection for juvenile fish from predators. The availability of lots of drifting seaweed or jellyfish can result in significant increases in the survival rates of some juvenile species.

Many coastal juveniles use seaweed for the shelter and the food that is available from invertebrates and other fish associated with it. Drifting seaweed, particularly the pelagic Sargassum, provide a niche habitat with its own shelter and food, and even supports its own unique fauna, such as the sargassum fish |

|

|