| GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDER

DISORDERS OF THE STOMACH

INDIGESTION/DYSPEPSIA

Top

Indigestion or dyspepsia is a general term that is frequently used to describe discomfort in the upper digestive tract.

Symptoms of dyspepsia

-

Vague abdominal pain

-

Bloating, nausea

-

Regurgitation

-

Belching

-

Dysphagia

Symptoms of prolonged dysphagia may be related to underlying problems, such as gastroesophageal reflux, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, delayed gastric emptying, gallbladder disease or cancer.

Patients who present with frequent or long standing dyspepsia are usually evaluated for more significant problems, but many persons have symptoms that persist despite lack of specific pathology. In patients with symptoms unrelated to a specific pathologic process, diet, stress, and other lifestyle factors may also play a role.

Nutritional care

Dietary indulgences-excessive volumes of food or high intake of fat, sugar, caffeine, spices, or alcohol, or both are commonly implicated in dyspepsia. Dietary management of uncomplicated dyspepsia is simple and has probably been passed on for generations; eat slowly, chew thoroughly and do not eat or drink excessively. Reaction to life stresses may also contribute to abdominal distress, in which case behavioral management and emotional support may also help. If symptoms persist despite these strategies, the individual may require further evaluation.

GASTRITIS AND PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Top

Gastritis and peptic ulceration may result when microbial, chemical, neural, or chemical abnormalities disrupt the factors that normally maintain mucosal integrity. The most common cause of gastritis and peptic ulcer is Helicobacter pylori infection. But chronic use of aspirin, alcohol abuse, ingestion of erosive substances or any combination of these factors may also be contributory. Tobacco product use, large doses of corticosteroids, and general poor health may contribute to the onset and severity of the symptoms.

The mucosa of the stomach and duodenum is normally protected from the proteolytic actions of gastric acid and pepsin by a coating of mucus secreted by glands in the epithelial walls from the lower esophagus to the upper duodenum. The mucosal layer is also protected from bacterial invasion by the digestive actions of pepsin and hydrochloric acid and the mucus secretions. The mucus contains acid neutralizing bicarbonates, and additional bicarbonates are provided by the pancreatic juice secreted into the intestinal lumen.

Production of mucus is stimulated by the action of prostaglandins. Hydrochloric acid is secreted by the parietal cells in response to stimuli by acetylcholine, gastrin and histamine.

GASTRITIS

Gastritis refers to the inflammation and tissue damage resulting from erosion of the mucosal layer and exposure of the underlying cells to gastric secretions and microbes. The most common cause of chronic gastritis is infection with H. pylori. The exposure results in general and specific inflammatory and immune responses to the gastric secretions and pathogens.

Acute gastritis refers to rapid onset of inflammation and symptoms.

Chronic gastritis may occur over a period of months to decades, with waxing and waning of symptoms.

Symptoms

-

Nausea

-

Vomiting

-

Anorexia

-

Haemorrhage

-

Epigastric pain.

Atrophic gastritis, which results in atrophy and loss of stomach parietal cells, is characterized by a loss of secretion of hydrochloric acid (achlorhydria) and intrinsic factor. Most cases are considered to have an autoimmune origin, although about 25% of cases may be a result of long term H. pylori infection.

Treatment of gastritis

The eradication of pathogenic organisms and withdrawal of any provoking agents. Antibiotics, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors may each play a role in the treatment of gastritis, depending on the precipitating cause. In individuals with atrophic gastritis, vitamin B12 status should be evaluated because a lack of intrinsic factor results in malabosorption of this vitamin.

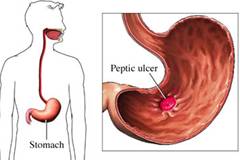

PEPTIC ULCER

Top

Peptic ulcer is a sore on the lining of the stomach where it joins the small intestine (duodenum). The stomach secretes various juices and acids that help in digestion of food. These acids are normally produced in the quantity that is needed to break down the food particles. Sometimes, when these acids are produced in excess, they erode the lining of the stomach and the duodenum resulting in ulcers.

The stomach is naturally protected from these acids by a mucous layer that covers it. The body secretes an alkali into this layer which neutralizes the acids and, thus, protects the stomach lining. A hormone-like substance called prostaglandin is also produced by the body that helps the blood vessels to expand and thus provide enough blood to the stomach. This also protects the stomach against injury.

Causes

Some of the major causes of peptic ulcers are

-

Bacterial infection – Helicobacter pylori bacteria is the major cause of stomach ulcers in most cases. This bacteria is also responsible for causing other conditions like stomach inflammation and cancer. It acts by causing changes in the individual's immune system and survives for most of the person's life.

-

Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) – Some medicines given to reduce pain may also cause stomach ulcers. Some of the common NSAIDs are aspirin, ibuprofen, nimesulide, diclofenac and naproxen. These medications reduce the production of prostaglandin to reduce pain. But in doing so, they also impair the natural protection of the stomach against the acids.

-

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome – in this condition, the pancreas produce excessive amounts of the hormone gastrin which stimulates the production of acids.

-

In rare cases, peptic ulcers may be caused due to physical injury to the concerned organs, increased consumption of alcohol and bacterial or viral infections.

Symptoms

Though some people may not experience any symptoms for a long time, some of the common signs of the condition are:

-

Dyspepsia – this includes a feeling of pain, bloating and discomfort in the stomach. This may be accompanied by nausea, heartburn and frequent belching.

-

Sometimes there may be severe abdominal cramps with blood in the stool.

Diagnosis

The disease is diagnosed by a thorough clinical history and examination. This includes recording the medications the patient is taking, any recent history of disease and any history in the family. In most cases, the doctor may prescribe acid blocking medication to see if the ulcers heal by themselves. If they still persist, then tests like endoscopy may need to be done. In this, a thin tube is inserted into the stomach to examine the damaged lining. In addition to this, a complete blood count (CBC) and a Stool occult blood test may be used to detect the pressure of blood in the stools.

Treatment

The treatment depends on the cause of the disease. If the cause is the use of NSAIDs, then they should be discontinued immediately. If the cause is h. pylori infection, then the doctor prescribes drugs like are omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin.

In some cases of bleeding ulcers, endoscopy is done in which the tubes inserted into the stomach coagulate the blood vessels with heat to stop the bleeding. In this surgical procedure called vagotomy, the nerve that transmits messages from the brain to the stomach to produce gastric acid is cut. This leads to reduction in acid production.

Changes in lifestyle needed

- Meals should be small so that the stomach lining is not unduly stretched.

- Consumption of milk, coffee and aerated drinks must be reduced.

- Diet rich in fibre and Vitamin A is helpful in reducing the risk of ulceration.

- Fruits with their skins must be consumed.

- Exercise may also reduce the risk of ulcer

Objectives

-

To provide adequate nutrition

-

To provide rest to the digestive tract

-

To maintain continuous neutralisation of gastric acid

-

To minimize acid secretion

-

To reduce mechanical, chemical and thermal irritation to the lining of the stomach

Dietary modifications

Energy: Patients suffering from peptic ulcers are undernourished and therefore, need an increased energy intake. In case of patients at bed rest, the energy needs for activity are not utilised and make up the extra needs.

Proteins: A high protein diet is advised as this promotes healing. Proteins also have a buffering action. Though milk protein has a good buffering action, the high calcium content of milk stimulates acid production. A high milk intake delays the healing of the ulcers and thus milk should be used in moderation. Eggs and other high protein foods can be included to meet the requirements.

Fat: Fat should be used in moderate amounts. Emulsified fats like butter, cream, etc. are better tolerated.

Carbohydrates: Carbohydrates are used to meet the energy needs. Foods containing harsh and irritating fibre should be avoided.

To remember

- Eat smaller meals

- Eat slowly

- Eat bland foods

- Avoid citrus fruits and juices

- Avoid coffee, tea and cola

- Avoid smoking

- Avoid stress

INTESTINAL GAS AND FLATULENCE

Top

Pathophysiology

Intestinal gases include nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide, hydrogen and in some individuals methane. About 200 ml of gas is normally present in the GI tract and humans excrete an average of 700 ml/day; however, there is a large range of volumes and excretion of gas in the GI tract. Considerable amounts of gas may be swallowed, exchanged between the GI tract and circulating blood and produced within the GI tract.

Gases taken in or produced in the gastrointestinal tract may be absorbed into the circulation and lost in respiration, expelled through eructation (belching) or passed rectally. When individuals complain about excessive gas, they may be referring to increased frequency of passage of gas or they may be complaining about the abdominal distention or cramping pain associated with the accumulation of gases in the upper or lower GI tract. The association between the amount of gas in the GI tract perceived by an individual and the amount actually measured is not always accurate. Inactivity, decreased GI motility, aerophagia (swallowing air), diet and GI disorders can all contribute to the amount of intestinal gas and the individual’s gas related symptoms.

When undigested carbohydrates pass into the colon, they are fermented, to varying degrees, to short chain fatty acids and gases, primarily hydrogen, carbon dioxide and in about one third of individuals methane. The widely recognized propensity of legumes to produce flatus or gas has been traced to the presence of specific indigestible carbohydrates, namely stachyose and raffinose. The properties of other so called gas forming foods may simply be related to the nature of the fibre and carbohydrate contents of the suspected foods, to odors produced or to individual responses to foods.

CONSTIPATION

Top

Pathophysiology

Constipation is characterized by hard stools, straining with defecation and infrequent bowel movements. At least in elderly patients, hard stool, incomplete evacuation and difficulty passing stools may be more troublesome than infrequency of bowel movements. One objective assessment defines constipation as a condition in which

-

Fewer than three stools per week are passed while a person is eating a high residue diet

-

More than 3 days go by without the passage of a stool and

-

The weight of stool passed in 1 day totals less than 35 g.

Normally stool weight is approximately 100 to 200 g/day and normal frequency may range from one stool every 3 days to three times per day. Normal transit time through the GI tract ranges from about 18 to 48 hours.

Persons consuming a diet containing the recommended amounts of dietary fibre in the form of fruits, vegetables, and whole grain breads and cereals tend to have larger, softer stools that are relatively easy to pass.

Causes

-

Lack of fibre in the diet,

-

Insufficient fluid intake,

-

Inactivity

-

Chronic use of laxatives.

-

Nervous strain or anxiety may aggravate the condition

Causes of Chronic constipation

1. Systemic

- Side effect of medication

- Metabolic and endocrine abnormalities – hypothyroidism, uremia

- Lack of exercise

- Ignoring the urge to defecate

- Vascular disease of the large bowel

- Systemic neuromuscular disease

- Poor diet – low in fibre

2. Gastrointestinal

-

Disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract – celiac, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, cystic fibrosis

-

Disease of the large bowel – failure of propulsion along the colon

-

Failure of passage through anorectal structures (outlet obstruction)

3. Irritable bowel syndrome

4. Hemorrhoids/ anal fissures

5. Laxative abuse

Treatment

-

Constipation is treated by including adequate dietary fibre, fluid and exercise in one’s daily routine and heeding the urge to defecate.

-

Patients with laxative habit should substitute progressively milder produces with an eventual goal of complete withdrawal.

-

Treatment of more resistant cases of constipation and of constipation related to functional bowel disorders may require intensive bowel training, chronic use of stool softeners and other medications, and various forms of surgical correction.

Nutritional care

An essential component of treatment for patients with constipation is provision of a normal diet that is high in both soluble and insoluble fibre. Diets low in fibre result in prolonged transit time through the gut, permitting excessive water reabsorption and the formation of hard stools.

Normal amounts of maldigested carbohydrate and fibre may help to hydrate stools and normalize bowel function, but excesses may also cause diarrhea. The primary effects of dietary fibre on bowel function relate to its water holding capacity, which presumably leads to larger, softer stools and its stretching effect on the distal colon and rectum, which increases the urge to defecate.

The daily diet should contain at least 25 g of dietary fibre, which can be supplied by including ample amounts of fruits, vegetables (especially legumes) and whole grains. Brans, such as wheat bran may be effective in promoting bulk formation and relieving constipation.

Laxatives

It is sometimes necessary to treat resistant constipation, as well as hemorrhoids, with substances that promote regular evacuation of soft stools. Bulking agents, such as cellulose, hemicellulose derivatives, psyllium seed and osmotic agents such as lactose, magnesium hydroxide and sorbitol have been used. Stool softeners, may also be used. Impactions of stool may require more stringent oral medications, rapid consumption of large volumes of fluids, enemas or digital evacuation.

DIARRHOEA

Top

Pathophysiology

It is characterized by the frequent evacuation of liquid stools, accompanied by an excessive loss of fluid and electrolytes, especially sodium and potassium. It occurs when there is excessively rapid transit of intestinal contents through the small intestine, decreased enzymatic digestion of foodstuffs, decreased absorption of fluids and nutrients or increased secretion of fluids into the GI tract. Diarrhoea often involves several of these mechanisms.

Osmotic diarrhoea are the result of active secretion of electrolytes and water by the intestinal epithelium.

Acute secretary diarrhoea are caused by bacterial exotoxins, viruses, and increased intestinal hormone secretion.

Exudative diarrhoea are always associated with mucosal damage, which lead to an outpouring of mucus, blood and plasma proteins, with a net accumulation of electrolytes and water in the gut. Prostaglandin release may be involved. The diarrhoeas associated with chronic ulcerative colitis and radiation enteritis are exudative.

Limited mucosal contact diarrhoea result from conditions of inadequate mixing of chime and inadequate exposure of chime to intestinal epithelium, usually because of destruction or a decrease in the mucosa as occurs in Crohn’s disease or following extensive bowel resection. This type of diarrhoea is usually complicated by steatorrhea resulting from bacterial overgrowth and by reduced luminal concentrations of conjugated bile acids.

Nutritional care

Because diarrhoea is a symptom of a disease state, the aim of medical treatment is to remove the cause. The next priority is to manage fluid and electrolyte replacement. Finally, attention must be given to nutrition concerns.

Adults

Nutritional care for adults with diarrhoea includes the replacement of lost fluids and electrolytes by increasing the oral intake of fluids, particularly those high in sodium and potassium such as broths and electrolyte solutions. Pectin from apple sauce, or a supplement and small amounts other hydrophilic fibre may also help in controlling diarrhoea.

When the diarrhoea stops and the patient begins to tolerate foods, the amounts given should be increased gradually as accepted, beginning with starches, which are likely to be well absorbed (e.g. rice, potato, plain cereals, etc.) and followed by protein foods. Fat need not be limited if the individual is otherwise healthy. Sugar alcohols, lactose, fructose and large amounts of sucrose may worsen osmotic diarrhoeas and may need to be limited. Because the activity of the disaccharidases and transport mechanisms may be decreased during inflammatory and infectious intestinal disease, sugars may need to be limited.

Severe and chronic diarrhea may be accompanied by dehydration and electrolyte depletion. If accompanied by prolonged infectious, immunodeficiency or inflammatory disease, malabsorptions of vitamins, minerals and protein and or lipid may also occur and the nutrients should be replaced parenterally or enterally. The loss of potassium alters bowel motility, encourages anorexia, and can introduce a cycle of bowel distress. Loss of iron from gastrointestinal bleeding may be severe enough to cause anaemia. The nutritional deficiencies themselves cause mucosal changes such as decreased villi height and reduced enzyme secretion further contributing to malabsorptions. As the diarrhoea beings to resolve, the addition of more normal amounts of fibre to the diet may help to restore normal mucosal function, increase electrolyte and water absorption and increase viscosity of the stool.

Infants and children

Acute diarrhoea is most dangerous in infants and small children, who are easily dehydrated by large fluid losses. In these cases, replacement of fluid and electrolytes must be aggressive and immediate. Standards oral rehydration solutions recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) contain a 2% concentration of glucose (20 g/L), 45 to 90 mEq/L of sodium, 20 mEq/L of potassium and a citrate base.

Oral rehydration solution

To 1 litre of water add the following

|

|

|

|

The solution should be made up fresh every 24 hours

|

STEATORRHEA

Top

Pathophysiology

It is a consequence of malabsorption in which unabsorbed fat remains in the stool. In contrast to the 2 to 6 g of ingested fat that is normally excreted each day as much as 60 g may be lost with this condition. With the exception of specific carbohydrate intolerances, almost all diseases causing malabsorption cause steatorrhea.

Nutritional care

Because steatorrhea is a symptom and not a disease, the underlying cause of malabsorption must be determined and treated. The presence of weight loss requires an increased energy intake. Dietary protein and carbohydrate should be high and fats may need to be added as tolerated to meet individual needs. Multiple vitamin and mineral deficiencies necessitate supplemental therapy, with special emphasis on fat soluble vitamins and minerals such as calcium, zinc, magnesium and iron.

Medium chain triglycerides

Inadequate energy intake resulting from faulty digestion and absorption of fat may be alleviated by the use of medium chain triglycerides (MTCs). These synthetic fats are made up of fatty acids that are 8 and 10 carbon atoms in length, compared with the 16 and 18 carbon chains common to most fatty acids that constitute dietary triglycerides. For this reason, MCTs are hydrolyzed more rapidly and can rely on the small amount of intestinal lipase available, rather than on pancreatic lipase for digestion. The products of hydrolysis are easily dispersed and absorbed in the absence of bile acids, which is often the cause of fat malabsorptions. Short chain fatty acids and medium chain fatty acids are able to enter the portal venous blood for direct transport to the liver without being resynthesized into triglycerides.

Source

Srilakshmi .B 2003.Dietetics, New Age International (P) Publishers Ltd.Chennai.

http://www.beliefnet.com/healthandhealing/images/si1454.jpg

http://www.doctorndtv.com/health/

http://www.medicinenet.com/dyspepsia/article.htm |